New Orleans Contraflow

Or, how I moved to the Ninth Ward eight days before Katrina and all I got was this sad little story

Here’s an audio version of the story that includes music.

Contraflow

A yellow Victorian. Fifteen-foot ceilings. L-shaped, with stoop and yard. Ornate trim, wrought iron. Dauphine Street. The Holy Cross subsection of the lower Ninth Ward. So close to the river you could walk up the raised bank and have your morning chicory still hot. By the specs, it’s still the best dwelling I’ve inhabited in my adult life.

I signed my lease and surrendered my first and last on August 21, 2005, in the lovely kitchen of the owners, a middle-aged couple who lived a few blocks away. A designer and a postman. I didn’t know them well and don’t even remember their names, but I remember being glad when they said we should have a cookout once I got settled in. I wanted to know them. I wanted to know everyone. I’d grown up in California, but New Orleans had felt like my city since the first time I set foot in it a couple years before. That immediate sense of home is a common feeling among those who move there. Now I was among them and I was elated.

First couple days, I spent a lot of time on my front porch. I gazed at the house across the street. It was in bad shape. The mother was incapacitated, her many children were kind. I got friendly with the young boy. He was maybe ten years old. We liked each other right off and made sure to wave and say hi. Little gestures of good faith that prop you up like stilts in a marsh. I don’t remember his name.

A semi-feral little Maine Coon kitten hung around my place, so I set about trying to coax her into friendship. I got some cat food and put it out with water in bowls. After a couple days, she knew I meant her no harm, and my heart swelled when after eating she would lay out on the other side of the stoop from me. No cuddles yet, but we were on our way.

My social club was the terminus or turnaround of St. Charles Avenue, the holy Circle Bar, so named for its being on Lee Circle, so named for Robert E. Lee, whose big statue stood right there. The statue pointed north so General Lee, a brief and failed leader of a foreign country, could look perpetually in the direction of his adversaries, or so his adversaries would never forget him. Agreement on the matter was never settled. They tore the old general down in 2017 and renamed the place Tivoli circle. Lest you cry out against the erasure of history, as if the whole South is still just the dying ember of Sherman’s bonfire, Tivoli was the circle’s original name. Its antebellum namers aspired to the civic gardens of Italy. The Lost Causers, though, seemed to think the eradication of slavery eradicated even the possibility of civic life along with it, so in 1877 they raised their symbol of perpetual grievance and changed the name. I wasn’t there when the statue was removed, but I can’t imagine it would have been difficult. Just sweep up the bottles and needles and other bonbons of despair, and tug.

The Circle Bar was a great place to see a live show and get to know your neighbors. You could hear the grunge country of the Happy Talk Band or the pristine Americana of Truckstop Honeymoon. You could hear metal, you could hear jazz. You could put Patsy Cline on the jukebox and learn where the riff-raff (hooray!) are gonna go next, or you could put a Marsalis on the box and learn finer points of the penal code from a defense attorney who’d just had a big week. Just down the street, you could dance to Kermit Ruffins!

On my second night as a starry-eyed resident of my adopted home city, I got to chatting with a woman with dreadlocks and a tattoo of a dragon or a snake on her leg. Her name was Dawn. She was beautiful–a gleaming friendly face like a saxophone or the Natchez steamboat that takes tourists and wedding parties up and down the river. She seemed to know everybody and I was delighted that she was talking to me. We met up later that week at the restaurant where she worked and agreed to meet again, but it would have to wait cause she was leaving the next day for a roller derby tournament in Las Vegas.

I went down to Houma to my buddy Claude’s trailer to learn how to make a proper roux. It surprised me at first that our soundtrack to the roux-making was Sade. Turns out Sade goes with everything. Claude’s instructions for a proper gumbo: never mix seafood and land animals. Do one or the other, but never both. The gods or the spirit of Jean Lafitte will have their revenge. It was like a Cajun version of the Hebrew prohibition against mixing milk and blood. Years later, in an ecstasy of contrarianism, I put shrimp and chicken in the same gumbo and have looked over my shoulder ever since.

Claude had been raised around Raceland, which he told me should actually be spelled “Ray’s Land” because it once belonged to Ray. I asked him how many times he’d had to evacuate for a hurricane.

“Never,” he said.

“Never? Not even once?”

“Never. It always misses us. Had some close calls…Betsy, Andrew…had to board up lots of times, but I never evacuated.”

Then he asked me if I wanted to go fishing on the afternoon of Saturday, August 27. I told him a friend from California and two friends from Lafayette would be coming down the day before to see my new place and help me with the heavy objects and he invited them too. They loved the idea, so our plans were all set.

That Saturday, the day of the fishing trip, Ryan, Mike, Allison and I went for breakfast at a small place on St. Charles. The eggs were good, but the mood of the joint seemed troubled. A group had formed around the TV in the corner and we joined them. “Hurricane coming,” said the news. “Big and fast. Landfall in about 48 hours. Mayor Nagin weighing mandatory evacuations.”

“What do we do?” asked my friends.

“I think we go fishing with Claude,” I said. “He’s never evacuated. But let me call him.”

He seemed surprised by the call. “You gotta get out of here,” he said. “Go. Board up your windows, pack up your things. Get out. This is the big one.”

“You’re evacuating?” I said.

“We’re packing up right now,” he replied.

We did not directly take Claude’s advice. We finished breakfast and strolled along St. Charles for a bit. Everything was weird and getting weirder. Everybody in every shop was watching the same news, talking about the same thing, changing their weekend plans. We got in my Honda station wagon and decided we should get some gallon jugs of water. Allison wanted to drive over to the lake. The radio reported that the parish mayors were issuing mandatory evacuations and the highways leading in and out of the city would now only lead out. Contraflow, they called it. It would double the egress capacity of the roads. My wife, a Katrina refugee who lost a hundred times more than I did, says the contraflow was an innovation borne from Hurricane Ivan, a near miss from the previous year. Without the contraflow lanes, it had taken her eight hours just to get to Baton Rouge. The lines at the gas stations were getting long.

It was a hot Saturday, as it should be in late August. But it was so still. Way too still. No breeze. Nothing moved. Bright blue sky and the shadows seemed fixed in place. My own movements didn’t feel right, like the normal pull of gravity or atmospheric pressure had either intensified or lessened. I couldn’t tell which. It was so still it was impossible to feel that it could ever change.

Somehow the four of us wandered to the mall along the river and watched Broken Flowers, the new Jim Jarmusch movie. Funny that watching Jim Jarmusch was a lunge for normalcy. Who knows. After the movie, Mike and Allison set out on the 100+ mile drive back to Lafayette. Ryan and I told them we’d go pack up my place and leave around dusk.

Ry and I delayed our work. We wandered around the French Quarter for a while. Most of the places were open, but foot traffic was low. Some drunk tourists still stumbled around, and the shops would still slosh you out a hurricane if you wanted it. Gallows humor–the most important humor there is–led us to Tower Records so we could buy Led Zeppelin IV for our drive. We wanted to blast “When the Levee Breaks,” not knowing that it would.

Dusk had arrived by the time Ry and I got back to Dauphine Street with our boards and boxes, but we still couldn’t bring ourselves to pack what we’d just unpacked. We took a beer each up the bank and sat on a bench looking southwest over the river. Here is where one of the strangest visions of my life occurred. Dusk had deepened. The whole sky was like the downcast amber face of a sultan below his purple turban, and the city lights were the pearls and diamonds in his ear and around his neck above his tunic’s dark silk. The sultan was sad and nervous, sinking down on his throne. He knew a time of change had come, and it had come unbidden by him.

As if out of some invisible celestial calliope came the distant tinkling of ragtime jazz, and Ry and I both pricked up our ears. Soon the source came into view. It was a steamboat with an open deck, merry as merry as could be. As it passed by, we saw the band and the revelers–dressed in full formal attire, tuxedos and evening gowns–dancing and spinning and drumming and trilling as if it were the last night of the world.

In another story about a flood, “The Deluge at Norderney” by the great Isak Dinesen,

…the romantic spirit of the age, which delighted in ruins, ghosts, and lunatics, and counted…a deep conflict of the passions a finer treat for the connoisseur than the ease of the salon and the harmony of a philosophic system…ladies and gentlemen of fashion abandoned the shade of their parks to come and walk upon the bleak shores and watch untameable waves. The neighborhood of a shipwreck where, in low tide, the wreck was still in sight, like a hardened, black, and salted skeleton, became a favorite picnic place, where fair artists put up their easels.

Dinesen adds, “By coming on in summer time, the deluge assumed the character of a terrible, grim joke.”

The party boat with the revelers looked like the ghosts of temporarily invigorated flesh and cloth draped upon the ever more indestructible skeletons, soon to be salted. We watched it fade around the riverbend. We said very little. Maybe a small toast. Finally, we packed.

By coming on in summer time, the deluge assumed the character of a terrible, grim joke.

-Isak Dinesen, “The Deluge at Norderney” from Seven Gothic Tales, 1934

Since I’d only been there six days, packing was nothing. I just filled the Honda right back up. The toughest part was trapping the cat. She seemed to know something was amiss, so she consented–I think for the first time–to being pet. I confirmed her worst fears and used her lowered defenses to abduct her, straight up. I threw her in a box where she, of course, writhed, so I threw the keys to Ryan, took the passenger seat, and brought her out of the box. She scratched my arm and hissed, then stilled as the frightened will when the hand’s around their neck.

As we pulled out, that ten year-old boy from across the street came over to the car. I asked if his mama would be evacuating the family. He looked at me like he had no idea why I would ask such a thing. I should have thrown my shit into the street and done something good for once. I should have ferried the family to some place or person who was not several feet below sea level as everyone in the Ninth Ward always is, but I was lazy and unimaginative, characteristics that are often one. I wished the kid the best and out we drove.

I named the cat Tipitina, after the great Professor Longhair song and Cajun palace on the corner of Napoleon and Tchoupitoulas. For short, I called her Tina. She remained in my lap as we drove on the eerie contraflow lanes and watched the cars on the other side of I-10 driving the same direction. The lines on the road were like a mirror image of reality–both the same and absolutely different. We arrived in Lafayette late and fell asleep quickly on the floor.

In the morning, we found the cat cowering in a corner. I had no litter box, so she’d need to go out. Somehow I thought she’d be a good little girl and come right back. She did not, and I spent the remainder of the day driving slowly around Lafayette looking for her and calling her by the name she did not know was hers. Sunday was a long day and dry. Seemed like all the rain had been sucked east.

The storm hit on Monday. It was bad, said the news, but not that bad. Could have been worse. What they didn’t realize, though, was the storm wasn’t the problem. The problem was the levees, which had not yet crumbled. The whole city was like Wile E. Coyote before looking down.

We were overstaying our welcome in Lafayette and Ryan needed to get back to Los Angeles. His flight, of course, had been canceled, and it was tough to find a replacement, so we drove. My roller derby queen with the dragon tattoo now seemed less like a romantic interest and more like an old friend who picked the exact right and the exact wrong week to go to Vegas, so I tried calling her. The cell lines were jammed–getting a call through to a New Orleans area code had become a long-odds game of chance.

In one moment of relief, as we were packing the car, little Tipitina appeared from under the deck of the house where she’d apparently done a real good job of hiding. Mike decided he’d keep her until I figured out where I lived. She was probably glad to see me go. As we drove, Ryan and I sang along to “When the Levee Breaks”, but when we put on Lucinda Williams’s “Jackson,” we went silent.

Once I get to Lafayette

I’m not gonna mind one bit

Once I get to Lafayette

I won’t mind one little bit

Once I get to Baton Rouge

I won’t cry a tear for you

Once I get to Baton Rouge

I won’t cry a tear for you

In the song, Lucinda’s driving east: Lafayette, Baton Rouge, Vicksburg, Jackson. We, having no other option, were driving west. Contraflow.

We were at a friend’s place in Denver when we learned the levees had broken. The early reports that the storm wasn’t as bad as it could have been were being revised, but everything was still so unclear. I’d hoped I could wait a couple days in Denver before heading back southeast, but that was not an option.

We arrived in Salt Lake City the next day around sundown. We got a room in a filthy hotel–some kind of roach-infested drug and prostitution den (can you believe such things happen in white cities, too?)–and went out to find something to eat. We saw a place called “The Bayou.” The Bayou in Salt Lake City. Fidelity to the god of gallows humor required us to go there and order something called jambalaya which to my tongue tasted like Hamburger Helper and pepperoni. We ate quietly while Ryan found a flight back to LA the next day.

My phone rang in the middle of the night and I picked it up. It was Dawn. She said she’d tried calling a couple times but could never get through. I said I’d done the same thing. She was distraught and asked me if I knew anything. I told her I didn’t. She had left her dog with a sitter somewhere around the French Quarter. “It’s higher ground, the dog will be fine, the dog will be fine,” we told each other.

“All I want is to be back home,” she said.

“They won’t even let you in,” I said.

“I know.”

She told me she didn’t have the money to continue staying in a Las Vegas hotel or any hotel for that matter. Some roller derby folks had tickets to and a campsite at Burning Man, so, oddly enough, that was the best option to buy some time until New Orleans opened back up. She gave me the campsite number and told me I was welcome to join them.

The next day, I dropped Ryan off at the airport and called the Burning Man offices. They told me I couldn’t come in without a ticket and tickets were no longer on sale. I pleaded my case, but they said I would be turned back at the gate. No one lost less than I did in that whole horrible fiasco, but being cast out of one place and not admitted to another felt like a double exile.

I should have gone home to Southern California. I could have been there in a day. But hadn’t I just left it? Wasn’t I supposed to be on an adventure? How could I simply return so soon and with so little evidence that I’d ever tried something? Further, we still didn’t know when New Orleans would open. The news was so confusing. I still had a lease.

First I drove back to Denver and stayed a few days. Then I drove to Chicago and did the same thing. Then to Cleveland for a month. I was a couchsurfing wipeout. I was in a haze. It was shock and grief and the guilt of a selective conscience, but I couldn’t name it. The blues is the best term. A piece of driftwood without rudder, now in a swirl, now rushing too fast, now stuck between a rock and Fats Domino’s piano.

Somewhere along the way that hot awful southern summer became a frigid awful northern winter. The bayous I’d sought were now industrial lakes. The honey-dipped garden terraces were steel-toed city tenements. The wonderful Circle Bar was now Becky’s, a pool joint across from the Greyhound Station where one did not go to know one’s neighbor, one went to obliterate one’s self. Or so it seemed to me.

Somewhere along the way my can-do spirit reversed. My sense of possibility became a sense of dread. Gallows humor became something between an earnest prayer and a wild wish, and that’s when you know you’re really lost.

Somewhere along the way the situation became clear—the lower Ninth was essentially destroyed. My house on Dauphine stood, but its insides and foundation were ruined. The pumps were struggling, water was stagnant. The blood and milk, chicken and shrimp got all mixed up with oil and rats and worse. The roof ripped off the dome. Thousands were dead. Thousands more displaced. Thousands more were starving. George Bush didn’t like black people. Brownie did a heckuva job. The saints did not come marching in, they were already there. But armed guards did come marching in, muzzles up, cause the real problem was the looting. Those newsmen and elected lawmen got their lanyards in a real twist about that. Just like they did every time before and every time since. The looting. Those animals. Same song, different station. We baptize our babies in the tears of General Lee and nothing makes him weep like the desecration of property.1

Meanwhile the insurers and incumbents met with lawyers to discuss their own catastrophe, which was whether the water had made the fine print run. “Some’ll rob you with a six gun, some with a fountain pen,” sang Woody Guthrie. We prefer the robbers with the fountain pens, but exceptions can be made. September 11th, 2001, had confirmed my suspicion that we still live in biblical times. Katrina confirmed to me that the Pharaohs still reign.

Somewhere along the way my savings had dwindled and there was no way I was getting my deposit back. Oh, I asked, you can be sure, selfish near-sighted solipsist that I am. Asking is how I know my landlords made it through. I hope they forgive me for the unforgivable question.

Somewhere along the way Dawn called me again. She asked if I’d tried to get to Burning Man. I told her I did. She told me her place in New Orleans was uninhabitable. I told her mine was too. I do not remember asking her about her dog. She said she was tending bar in exchange for a room in Montana. Or Alaska. I can’t remember. I wished her well, then lost her number and never spoke with her again.

By mid-December I was apartment-sitting in Brooklyn. Friends were kind, but I couldn’t connect to them. I got in my Honda and drove. Somewhere in a fast-rising midday blizzard around St. Louis my tires locked up and I drifted, slowly, even peacefully, with no capacity and very little desire to control the slide, into a snowbank off the shoulder. The kind and talented towing man pulled me out with a smile and a “No problem!” and I felt better than I had in months. I stayed that night at a motel with a margarita bar that was absolutely slamming. I liked watching from a distance as folks enjoyed themselves as if nothing else was going on at all.

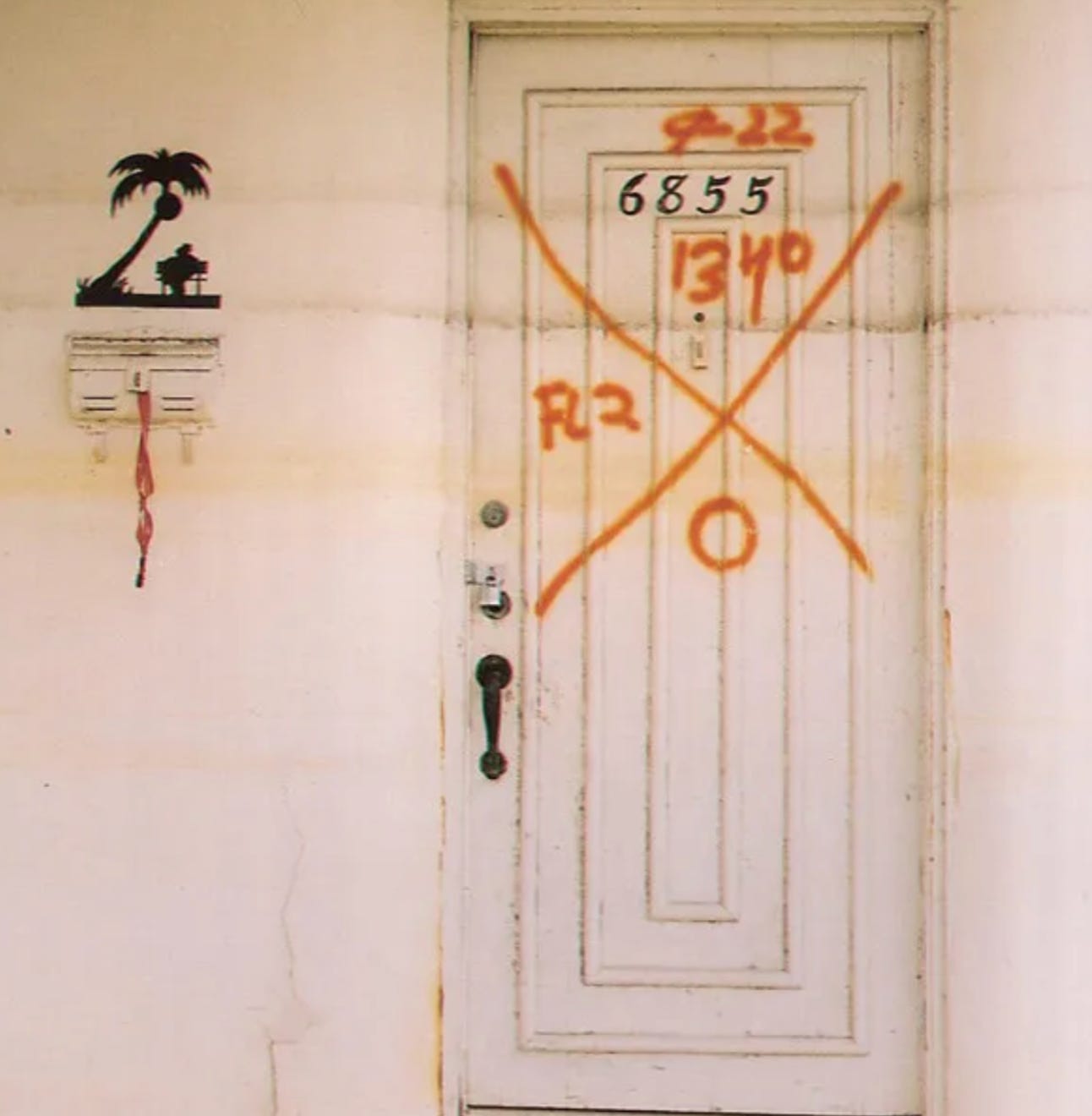

I got up before dawn the next morning. Instead of taking the direct route west, I went South on 55. New Orleans had opened and I wanted to see it. I arrived in the early afternoon and drove slowly through town. It’s a mausoleum city, but now the cemeteries had no walls. I crossed the Bywater bridge over the industrial canal into the Ninth Ward and went to Dauphine Street. Instead of the Christmas wreath I would have assuredly put on the door there was the spray-painted X-code, or the Katrina Cross as some locals call it.2 An X with a code in each quadrant.

I did not know what the code meant, and I learned later that confusion about the code was common. It was meant to inform that a dwelling had been inspected and what the inspection had found. The lowest quarter meant that my body had not been found. A different code from a different team meant that Tina’s body had not been found. The house across the street where my young pal lived did not have an X-code on the house, because there was no longer a house. A big tree–live oak, pecan, I don’t know–had smashed down right through the middle of it.

It is strange to stand in a place where something once had happened. Strange to find the seashell on the desert floor, the arrowhead on the plain, the shipwreck on the mountaintop. I did not stay long on Dauphine Street that day.

In another flood story, The Wild Palms, or If I Forget Thee, Jerusalem, Faulkner imagines the 1927 flood zone thus:

It was as if the water itself were in three strata, separate and distinct, the bland and unhurried surface bearing frothy scum and a miniature flotsam of twigs and screening as though by vicious calculation the rush and fury of the flood itself, and beneath this in turn the original stream, trickle, murmuring along in the opposite direction, following undisturbed and unaware its appointed course and serving its Lilliputian end, like a thread of ants between the rails on which an express train passes, they (the ants) as unaware of the power and fury as if it were a cyclone crossing Saturn.

Contraflow.

New Orleans is a bowl. Stilts prop it up, levees and pumps are meant to keep it dry. But Monique Verdin, a Houma photographer, calls it a “cement lily pad,” and Rebecca Snedeker uses the metaphor to imagine a possible future in which New Orleans can become something closer to that, something closer to Rotterdam, less intent on pumping out than on floating upon.3

I drove to the Circle bar and went inside. There were no bohemians, no music. Just a row of contractors at Christmastime drinking Budweiser and speaking Spanish quietly. If anybody deserved the quiet and the beer, they did. I talked to the bartender with tired eyes who’d only been back a couple weeks. He said some of the regulars had come back, and they were trying to pass a good time, as they say down there, but things were rough. To pass a good time is not to pass up a good time or to take a pass on a good time. It is, I like to think, to pass it around, to pass it on, like a communion chalice or a good joke. That’s part of what I had come there to do, but the cup was passed from me, mercifully, I suppose, before I had to pray that it would.

Gallows humor: the drink special on offer was the “Na-Gin & Tonic,” so named for Ray Nagin, the mayor of New Orleans during Katrina, the man who waited, then hid, then went to jail for fraud. I thanked the bartender for the coffee and got on the road to Lafayette.

Somewhere in the loneliness of the nighttime Atchafalaya swamp, about an hour into my drive, I got a hankering and gave the Circle Bar a call. The bartender answered and I asked if anybody had spoken to Dawn, a woman with a tattoo on her leg who last I heard was in Montana. “She was just here,” he said. “Left about half an hour ago.” I didn’t go back, I was just glad my friend got back home safe.

I slept that night in Lafayette and left the next morning. I abducted poor Tipitina for the final time and was home in Southern California in a couple days. Tina took to my dad, so she stayed with my parents while I moved on to start over at starting over. Tina’s been gone for years now. I like to think the good Lord put her on his lap in paradise and explained to her what had really happened and what it all meant.

“We gotta carry New Orleans with us,” my wife always says. We go back when we can, and on one trip some years ago we decided to drive to the end of the road. Down LA 23 along the river through Placquemines Parish, where the houses raise up on stilts and the stilts get taller the further you go. Belle Chasse, Port Sulphur, Buras and Triumph (where Katrina first touched down), all the way to Pilottown, which was once the headquarters of the boat pilots. Bananas in, sugar out.

We drove as far as we could on four wheels. Any farther and we’d need a boat. The road did not so much end as it descended, limp and without fanfare, into water. Not roaring water, no crashing waves or Saturnine storms, not even a beach or a view, just one curious little tongue of a many-headed beast sneaking up from the swamp and lapping like a kitten at her bowl. We got out and walked around. All we saw was a small power plant and a solitary cow. Maybe the cow was an adventurer, seeing how far he could go. Maybe it was the Egyptian goddess Hathor, deity of motherhood, love, joy, and the sky, the one who nourishes the dead.

Floodlines, a superb audio documentary by Vann Newkirk II and The Atlantic, reveals how quickly the newsmen and elected officials—none of whom were on the ground—accepted monstrous fictions of looting, murder, rape, and sabotage. It seems that the same people saying “We’re hungry” day after humid day did not provide enough narrative arc to sustain viewership or the attention of the representative government. Do not miss the interview with Michael Brown in Episode VIII. https://www.theatlantic.com/podcasts/floodlines/

Dorothy Moye. The X-Codes: A Post-Katrina Postscript. https://southernspaces.org/2009/x-codes-post-katrina-postscript/

Snedeker’s essay appears in Unfathomable City, a book of essays and atlases on New Orleans edited by Snedeker and Rebecca Solnit. It would be one of the first items I’d grab if I ever have to make another hurried exit. Fans of M.E. Rothwell’s Cosmographia will love this book.

The audio version takes you on the journey to that time.

Poignant and powerful recollection. Definitely worth reading over and over as you let the emotion of it sink in.